COGNEX: WHAT IS THE PATMAX TOOL AND IMPORTANT ROLE OF MACHINE VISION

Industrial robots ask a lot of questions. Where is the next part on their digital to-do list? How can they tell one part from another? Where should a part go after it’s been located and identified?

Pattern-matching software answers these queries. How does it work, and why is it a crucial component of machine vision? An excellent way to understand pattern matching is to explore how PatMax, one of Cognex’s most powerful tools, enables automation in a wide range of industries. Read on for a quick introduction.

PatMax Tool: The Pattern-Matching Basics

Before we look at the industries, let’s examine what the PatMax tool does. PatMax starts with a “training image” — a digital photograph of a machine part, product component or any other object that an automated system has to deal with.

PatMax scans the image for edges that identify geometrical shapes. These shapes become a kind of digital signature which, for instance, teaches a computer to know that a round mass of steel on a Detroit assembly line is a brake disc and not a brake drum. An industrial robot uses the PatMax signature to find the right disc, grab it and insert it on the car-to-be where it belongs.

Specialized industrial cameras are the robot’s eyes. They scan parts that the robot will fetch from a bin or conveyor and then attach to other parts. PatMax creates tables of digital data that rapidly memorize geometric shapes and use pattern matching to prevent the robot from picking the wrong part or putting a part in the wrong place.

PatMax Inspections in Five Industries

Automotive: Cars and trucks have some of the most sophisticated assembly lines. That’s why robots have taken over so many automotive manufacturing chores. PatMax can do basic pattern matching, like determining whether a wheel has a four- or a five-bolt lug pattern. It can also do complex functions like ensuring that entire trim packages — tires, transmissions, paint and infotainment, for instance — come together properly on each vehicle.

PatMax in automotive inspection

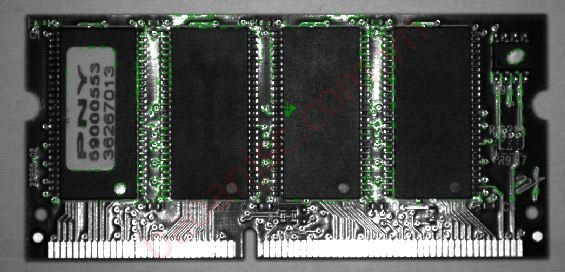

Consumer electronics: Devices like smartphones cram hundreds of components into extremely tight spaces. Typically, they are constructed in layers that require precise alignment. Robust pattern-matching software can identify all the geometric shapes on a circuit board, battery and display screen. With these patterns in hand, an industrial robot can line everything up, apply adhesives and paint coatings, and reduce the potential for human error.

Food and beverage: Ice cream provides the tastiest example. PatMax can take digital images of the ice cream carton and correlate them with the proper ingredients — nuts, fruit, chocolate chunks and such. On a production line, this ensures that ice cream flavor inside always squares with the information on the label. The same concept applies across the food-and-beverage sector. Bottle shapes, box labels and major ingredients all can be digitized into geometric patterns that ensure production accuracy and improve efficiency.

PatMax in electronics inspection

Medical/pharmaceutical: The tiny opening on a hypodermic needle is cut to an exact size at an optimum angle. The components of an artificial hip joint require a precise fit. A prescription must include a booklet with instructions and precautions. A barcode should be in the same place on every box. PatMax can ensure that production systems meet these and many more parameters. One of the core functions is registration — creating geometric shapes that allow robots to align multiple elements.

Semiconductors: An integrated circuit is one of the world’s most delicate manufactured products. It has to be built with extreme care and precision to protect the viability of millions of microscopic transistors etched in silicon. PatMax got its start in the semiconductor sector more than 20 years ago. The software helps manufacturers identify the structures within computer chips and find the exact points for cutting or assembling.

A precise pattern matching tool for an exacting job

The PatMax tool is just one component of an effective machine vision system. For best performance, it has to be properly integrated into a system of cameras, software and robotic processes. PatMax is ideal for difficult manufacturing environments where ambient lighting, reflective parts and uneven surfaces confound lesser systems.

Source: Cognex

For more information:

- Address: Vân Tra, An Đồng, An Dương, Hải Phòng city

- Hotline: 0936.985.256

- Website: https://baoanjsc.com.vn

- Email: baoan@baoanjsc.com.vn.

- Fanpage: https://www.facebook.com/BaoAnAutomatio